:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/behavioraleconomics.asp-final-10e6085b26754eea8b50bc54882a1b8a.png)

Behavioral economics

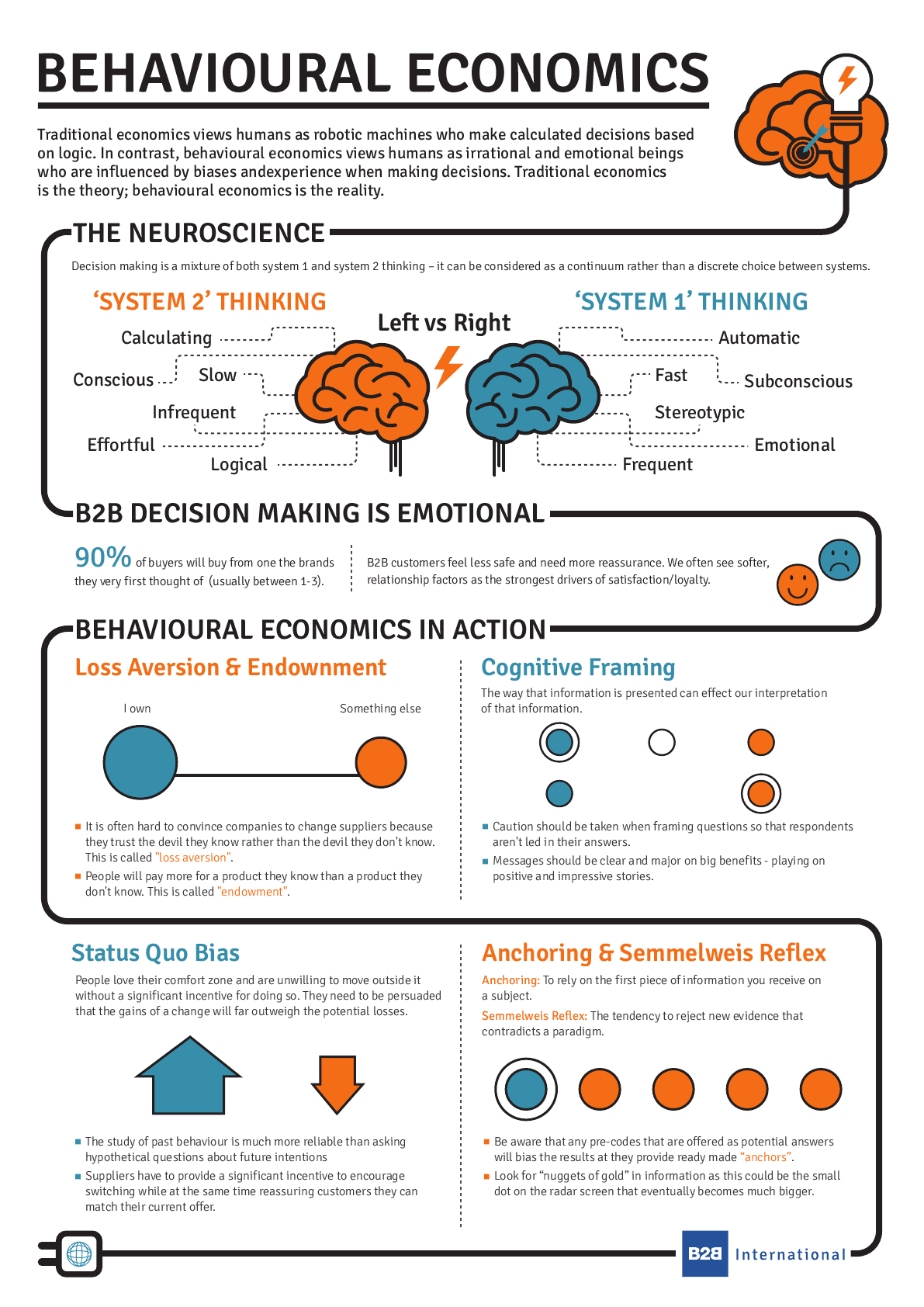

Behavioral economics is essentially the study of how people actually make decisions, rather than how they should make them according to traditional economic models.

Traditional economics assumes people are rational, logical beings who always make choices that maximize their own self-interest. But in reality, our decisions are heavily influenced by psychological factors, emotions, and social pressures.

The Endowment Effect: Why We Overvalue What We Own

Imagine you bought a concert ticket for $100. The day of the concert arrives, and you realize you’re not feeling well. You’d probably be reluctant to sell the ticket for even slightly less than you paid, even if it means missing out on the concert entirely.

This is the endowment effect in action. Once we own something, we tend to value it more than we would if we were considering buying it. We become emotionally attached and overestimate its worth.

Loss Aversion: The Fear of Losing Out

We feel the pain of a loss much more intensely than the pleasure of an equal gain. This is known as loss aversion.

For example, losing $100 feels worse than the joy of finding $100. This principle is exploited by marketers in many ways, such as emphasizing limited-time offers or highlighting the potential for “missing out.”

Framing Effects: How the Presentation Influences Our Choices

The way information is presented can significantly impact our decisions. This is known as the framing effect.

Example 1:

Example 2:

The Anchoring Effect: How Initial Information Influences Our Decisions

The anchoring effect occurs when our initial exposure to information significantly influences our subsequent judgments, even if that initial information is irrelevant.

The Availability Heuristic: Overestimating the Likelihood of Vivid Events

We tend to overestimate the likelihood of events that are easily recalled or come readily to mind. This is the availability heuristic.

Social Proof: Following the Crowd

We often make decisions based on what others are doing. This is the principle of social proof.

The Sunk Cost Fallacy: Throwing Good Money After Bad

The sunk cost fallacy refers to our tendency to continue investing in something, even when it’s clearly not a good decision, simply because we’ve already invested time or money in it.

The Status Quo Bias: Sticking with the Familiar

We often prefer to maintain the status quo, even when there might be better alternatives available. This is the status quo bias.

The Halo Effect: Judging People Based on One Trait

The halo effect occurs when our overall impression of a person influences how we perceive their other qualities.

The Horns Effect: The Opposite of the Halo Effect

The horns effect is the opposite of the halo effect. If we have a negative initial impression of someone, we may tend to perceive them negatively in other areas as well.

The Bandwagon Effect: Joining the Crowd

The bandwagon effect describes our tendency to conform to the beliefs or behaviors of the majority, even if we don’t necessarily agree with them.

The IKEA Effect: Overvaluing Things We Build Ourselves

The IKEA effect refers to our tendency to overvalue things that we have created or assembled ourselves, even if they are not particularly well-made.

The Paradox of Choice: Too Many Options Can Lead to Overwhelm and Inaction

While having choices may seem like a good thing, too many options can actually lead to indecision and even regret. This is known as the paradox of choice.

The Planning Fallacy: Underestimating How Long It Will Take to Complete a Task

We often underestimate the time and effort required to complete a task, even when we have previous experience with similar tasks. This is known as the planning fallacy.

The Optimism Bias: Believing We Are Less Likely to Experience Negative Events

We tend to be overly optimistic about the future and underestimate our own vulnerability to negative events. This is known as the optimism bias.

The Confirmation Bias: Seeking Out Information That Confirms Our Existing Beliefs

We tend to seek out information that confirms our existing beliefs and ignore or downplay information that contradicts them. This is known as the confirmation bias.

The Self-Serving Bias: Attributing Success to Ourselves and Failures to External Factors

We tend to attribute our successes to our own skills and efforts, while blaming external factors for our failures. This is known as the self-serving bias.

The Endowment Effect in Action: Marketing and Pricing Strategies

Marketers often exploit the endowment effect to increase sales. For example:

Free trials: Offering free trials allows customers to experience a product or service, making them more likely to value it and purchase it later.

Loss Aversion in Marketing: The Fear of Missing Out (FOMO)

Marketers frequently leverage loss aversion to drive sales. For example:

Limited-time discounts: Creating a sense of urgency and the fear of missing out on a good deal.

Framing Effects in Marketing: How to Present Your Products and Services

Focus on the positive: Frame your products and services in a positive light, emphasizing their benefits and advantages.

The Anchoring Effect in Negotiations: Setting the Initial Price

The Availability Heuristic and News Media: The Power of Vivid Stories

News media often relies on the availability heuristic to capture our attention. Vivid and emotionally charged stories, even if they are rare or unlikely, are more likely to be reported and remembered.

Social Proof in Marketing: Leveraging Testimonials and User Reviews